D.J. Field, M. Hanson, D. Burnham, L.E. Wilson, K. Super, D. Ehret, J. Ebersole & B.-A.S. Bhullar, published in Nature, volume 357, 3May2018.

The skull of living birds is greatly modified from the condition found in their dinosaurian antecedents. Bird skulls have an enlarged, toothless premaxillary beak and an intricate kinetic system that includes a mobile palate and jaw suspensorium. The expanded avian neurocranium protects an enlarged brain and is flanked by reduced jaw adductor muscles. However, the order of appearance of these features and the nature of their earliest manifestations remain unknown. The Late Cretaceous toothed bird Ichthyornis dispar sits in a pivotal phylogenetic position outside living groups: it is close to the extant avian radiation but retains numerous ancestral characters. Although its evolutionary importance continues to be affirmed, no substantial new cranial material of I. dispar has been described beyond incomplete remains recovered in the 1870s. Jurassic and Cretaceous Lagerstätten have yielded important avialan fossils, but their skulls are typically crushed and distorted. Here we report four three-dimensionally preserved specimens of I. dispar— including an unusually complete skull—as well as two previously overlooked elements from the Yale Peabody Museum holotype, YPM 1450.

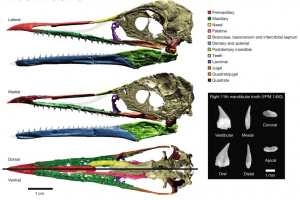

We used these specimens to generate a nearly complete three-dimensional reconstruction of the I. dispar skull using high resolution computed tomography. Our study reveals that I. dispar had a transitional beak—small, lacking a palatal shelf and restricted to the tips of the jaws—coupled with a kinetic system similar to that of living birds. The feeding apparatus of extant birds therefore evolved earlier than previously thought and its components were functionally and developmentally coordinated. The brain was relatively modern, but the temporal region was unexpectedly dinosaurian: it retained a large adductor chamber bounded dorsally by substantial bony remnants of the ancestral reptilian upper temporal fenestra. This combination of features documents that important attributes of the avian brain and palate evolved before the reduction of jaw musculature and the full transformation of the beak.